![]() Growing up in Paris and the South of France, Jean-Pierre Sylvestre developed a passionate interest in two hobbies at a very young age – dinosaurs and sea creatures. Among those fortunate few who are able to translate their youthful obsessions into well-respected careers, he is today one of the world’s foremost marine photojournalists and a prolific book author on marine mammals. With 25 years of experience in documenting and reporting on this fascinating subject, he has traveled from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and a great many places in between.

Growing up in Paris and the South of France, Jean-Pierre Sylvestre developed a passionate interest in two hobbies at a very young age – dinosaurs and sea creatures. Among those fortunate few who are able to translate their youthful obsessions into well-respected careers, he is today one of the world’s foremost marine photojournalists and a prolific book author on marine mammals. With 25 years of experience in documenting and reporting on this fascinating subject, he has traveled from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and a great many places in between.

After leaving school and serving in the French Navy, Jean-Pierre had dreams of becoming a marine mammal biologist. However, while working for eight years at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, he decided that this was not the path his career should take. Though he was already publishing articles based on the laboratory research of whales and sharks, he realized, “I am happiest in the field loaded down with my cameras, not in the laboratory. I have no patience staying in one place, so it seemed a more satisfying direction to become a wildlife photographer and reporter. In that role, unlike being a scientist, I have nothing to prove or justify – what I observe is all that matters.”

The biggest challenge with marine photography, says Jean-Pierre, is first finding the subjects at all in the vast ocean-based environment, and then coping with the currents, weather, and constant movement, always working against good pictures. “Humans are not aquatic by nature, so it is difficult for them to function in what is an alien environment.”

Our photographer has written over 400 articles for French-speaking magazines and newspapers in Europe and Quebec and researched 23 authoritative books. These richly illustrated references include one on whales, one on dolphins and porpoises, one on seals and manatees, and one on Canadian marine mammals.

And let’s not forget that other youthful interest – dinosaurs. Jean-Pierre remains only slightly less passionate about dinosaurs and other vertebrate fossils, including woolly mammoths. You may be sure that his globetrotting itineraries in search of marine life also include many detours to dig sites and paleontology museum collections to document discoveries in print articles and on film.

Home base for Jean-Pierre is Rimouski, Quebec. However, no matter where in the world he is researching, thanks to his email, orcajps@hotmail.com, this photojournalist is usually within contact, except when under water clad in scuba diving gear and trailing his waterproof cameras.

Sea Otter

I have found that a sea kayak is the best way to approach some shy sea mammals because it is quiet, low in the water, and unthreatening. This sea otter in Monterey Bay, California, was quite happy to bob in the kelp while I photographed her very closely, but I constantly worried about my cameras which were always in danger of slipping overboard in a kayak. It is easy to identify the female sea otter because of the nose bites that the male gives her during mating.

I have found that a sea kayak is the best way to approach some shy sea mammals because it is quiet, low in the water, and unthreatening. This sea otter in Monterey Bay, California, was quite happy to bob in the kelp while I photographed her very closely, but I constantly worried about my cameras which were always in danger of slipping overboard in a kayak. It is easy to identify the female sea otter because of the nose bites that the male gives her during mating.

Greenland Harp Seal

In Quebec’s Magdalen Islands, north of Prince Edward Island, where this photograph was taken, the temperatures can dip to minus 45 degrees centigrade with wind chill. You can see ice on the whiskers of this mother Greenland harp seal with her week-old baby. March is the best time to view these seals on the ice. The film often suffers in very cold weather, so it is best to keep the camera inside your survival suit when you are not clicking pictures.

In Quebec’s Magdalen Islands, north of Prince Edward Island, where this photograph was taken, the temperatures can dip to minus 45 degrees centigrade with wind chill. You can see ice on the whiskers of this mother Greenland harp seal with her week-old baby. March is the best time to view these seals on the ice. The film often suffers in very cold weather, so it is best to keep the camera inside your survival suit when you are not clicking pictures.

Commerson’s Dolphin

Though little is known about this dolphin which makes its home in the icy waters between South America, the Falkland Islands, and Antarctica, this small member of the dolphin family has distinctive camouflage markings. From above, its solid black back makes the dolphin virtually invisible; from below, its white underside makes the animal equally hard to see against the brightness of the water’s surface. In this photo, it is “spy hopping” or checking out its surface surroundings at a vertical angle, like a periscope. This is a practice common to all dolphins and whales.

Though little is known about this dolphin which makes its home in the icy waters between South America, the Falkland Islands, and Antarctica, this small member of the dolphin family has distinctive camouflage markings. From above, its solid black back makes the dolphin virtually invisible; from below, its white underside makes the animal equally hard to see against the brightness of the water’s surface. In this photo, it is “spy hopping” or checking out its surface surroundings at a vertical angle, like a periscope. This is a practice common to all dolphins and whales.

Alaska Pacific Walrus

I took this photo of Alaska Pacific walrus on the very remote Round Island in Alaska’s Bering Sea. Only the males come here by the thousands to relax. It is their holiday island where they go for rest and recreation and companionship when they are not aggressively protecting their harems from each other during mating season.

I took this photo of Alaska Pacific walrus on the very remote Round Island in Alaska’s Bering Sea. Only the males come here by the thousands to relax. It is their holiday island where they go for rest and recreation and companionship when they are not aggressively protecting their harems from each other during mating season.

Beluga Whale

I have tried to dive with beluga whales, but they are very shy and usually slip away. They do like the movement of a boat and will swim with it without alarm, but if the boat stops, they immediately move away. I find Belugas, like this one near Churchill in the Hudson’s Bay, quite easy to photograph because they are such a sharp white contrast to the water.

I have tried to dive with beluga whales, but they are very shy and usually slip away. They do like the movement of a boat and will swim with it without alarm, but if the boat stops, they immediately move away. I find Belugas, like this one near Churchill in the Hudson’s Bay, quite easy to photograph because they are such a sharp white contrast to the water.

False Killer Whale

As this dolphin surfaces to breathe, three-quarters of its head appears above water. It is a very “cosmopolitan” species found in the temperate and tropical climates. In length, adults are about five meters [16 feet], and, unlike their distinctively marked black and white cousins, the orcas, they are solid black. This is why sailors called them false killer whales. Their prime cause of mortality is spectacular mass groundings where several hundred animals beach themselves – the record was 800 strandings on the Argentine coast in 1964. Scientists have no clear answer for this behavior.

As this dolphin surfaces to breathe, three-quarters of its head appears above water. It is a very “cosmopolitan” species found in the temperate and tropical climates. In length, adults are about five meters [16 feet], and, unlike their distinctively marked black and white cousins, the orcas, they are solid black. This is why sailors called them false killer whales. Their prime cause of mortality is spectacular mass groundings where several hundred animals beach themselves – the record was 800 strandings on the Argentine coast in 1964. Scientists have no clear answer for this behavior.

West Indies Manatees

During the cooler Florida winter months, manatees congregate around the warm river estuary springs north of Tampa and St. Petersburg. Manatees are very trusting, so I swam with this mother and baby for four hours playing with the baby and scratching the mother who was about 400 kilograms [900 pounds] and two meters [6.5 feet] in length. The baby wanted to be so close to me all the time that I had to keep pushing him away in order to take pictures.

During the cooler Florida winter months, manatees congregate around the warm river estuary springs north of Tampa and St. Petersburg. Manatees are very trusting, so I swam with this mother and baby for four hours playing with the baby and scratching the mother who was about 400 kilograms [900 pounds] and two meters [6.5 feet] in length. The baby wanted to be so close to me all the time that I had to keep pushing him away in order to take pictures.

Polar Bear

For the past 25 years, polar bears have been recognized as a marine mammal by scientists because they spend 20 – 30% of their time in the water. My Inuit guide and I spotted this bear swimming in Hudson Strait off the northern tip of Quebec facing Baffin Island. My guide wanted to kill it, but I insisted most forcefully that I wished to photograph it both in the water and on the ice, so its life was saved for that day at least.

For the past 25 years, polar bears have been recognized as a marine mammal by scientists because they spend 20 – 30% of their time in the water. My Inuit guide and I spotted this bear swimming in Hudson Strait off the northern tip of Quebec facing Baffin Island. My guide wanted to kill it, but I insisted most forcefully that I wished to photograph it both in the water and on the ice, so its life was saved for that day at least.

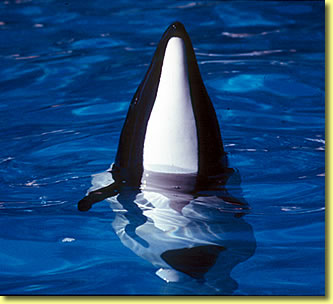

Killer Whale

The killer whale’s generic scientific name is Delphinus orca or demon dolphin, which says a lot about the way humans have viewed this species over the centuries. It is easy to identify with a high dorsal fin, dramatically colored body, and large size. I am very attached to this powerful, clever species which always gives me such pleasure to photograph all over the world. Since it was the first cetacean species I ever saw in the wild, I have adopted it as my company’s logo.

The killer whale’s generic scientific name is Delphinus orca or demon dolphin, which says a lot about the way humans have viewed this species over the centuries. It is easy to identify with a high dorsal fin, dramatically colored body, and large size. I am very attached to this powerful, clever species which always gives me such pleasure to photograph all over the world. Since it was the first cetacean species I ever saw in the wild, I have adopted it as my company’s logo.

![]()

Naturalist and photographer, Jean-Pierre Sylvestre, has also contributed another article to our web magazine, in which he encounters plenty of grizzly bears, killer whales and unexpected adventures when he visits British Columbia’s remote Knight Inlet Lodge floating on the sea.

Naturalist and photographer, Jean-Pierre Sylvestre, has also contributed another article to our web magazine, in which he encounters plenty of grizzly bears, killer whales and unexpected adventures when he visits British Columbia’s remote Knight Inlet Lodge floating on the sea.

And don’t miss another richly illustrated article about taking a marine wilderness vacation to a sheltered Vancouver Island seaway nicknamed the Serengheti Plains of the marine world, for the abundance and diversity of marine life to be witnessed up close in the waters of the same region of British Columbia!

Photo Quest Adventures offers deluxe global photography workshops to the world’s most photogenic corners taught by the best photographers. We distinguish ourselves by offering innovative and intimate workshops geared for small groups over 50 years old, all skill levels to ensure individual attention. www.photoquestadventures.com.

Photo Quest Adventures offers deluxe global photography workshops to the world’s most photogenic corners taught by the best photographers. We distinguish ourselves by offering innovative and intimate workshops geared for small groups over 50 years old, all skill levels to ensure individual attention. www.photoquestadventures.com.